Microsoft Flight Simulator and its successor Microsoft Flight Simulator 2024 have brought the use of geospatial data under the spotlight of flight simulation and gaming.

Yet, this kind of technology and data application has been part of the history of simulation for a long time, and, of course, they also have extensive applications in business and research outside of gaming and simulation, including the creation of the much-discussed digital twins.

Here at Simulation Daily, we have access to Orbx’s professionals to provide you with some interesting insight into how the cake is made. To hear more about the many facets of Geospatial data and its applications, we had a chat with Holger Sandmann, Head of Geospatial at Orbx.

Giuseppe Nelva: Head of Geospatial is certainly an interesting title. Could you introduce your role at Orbx?

Holger Sandmann: It does make for interesting introductions. Since the genesis of Orbx, back in 2006, landscape sceneries have been the cornerstone of our product range.

These regional or global add-ons require the discovery and processing of large quantities of geospatial data – elevation, shorelines, road network, vegetation, land use information, etc. Typically, this involves teams of several people and, for some time now, I’ve been the leader of these teams.

Giuseppe: How does Orbx use geospatial data to create its products?

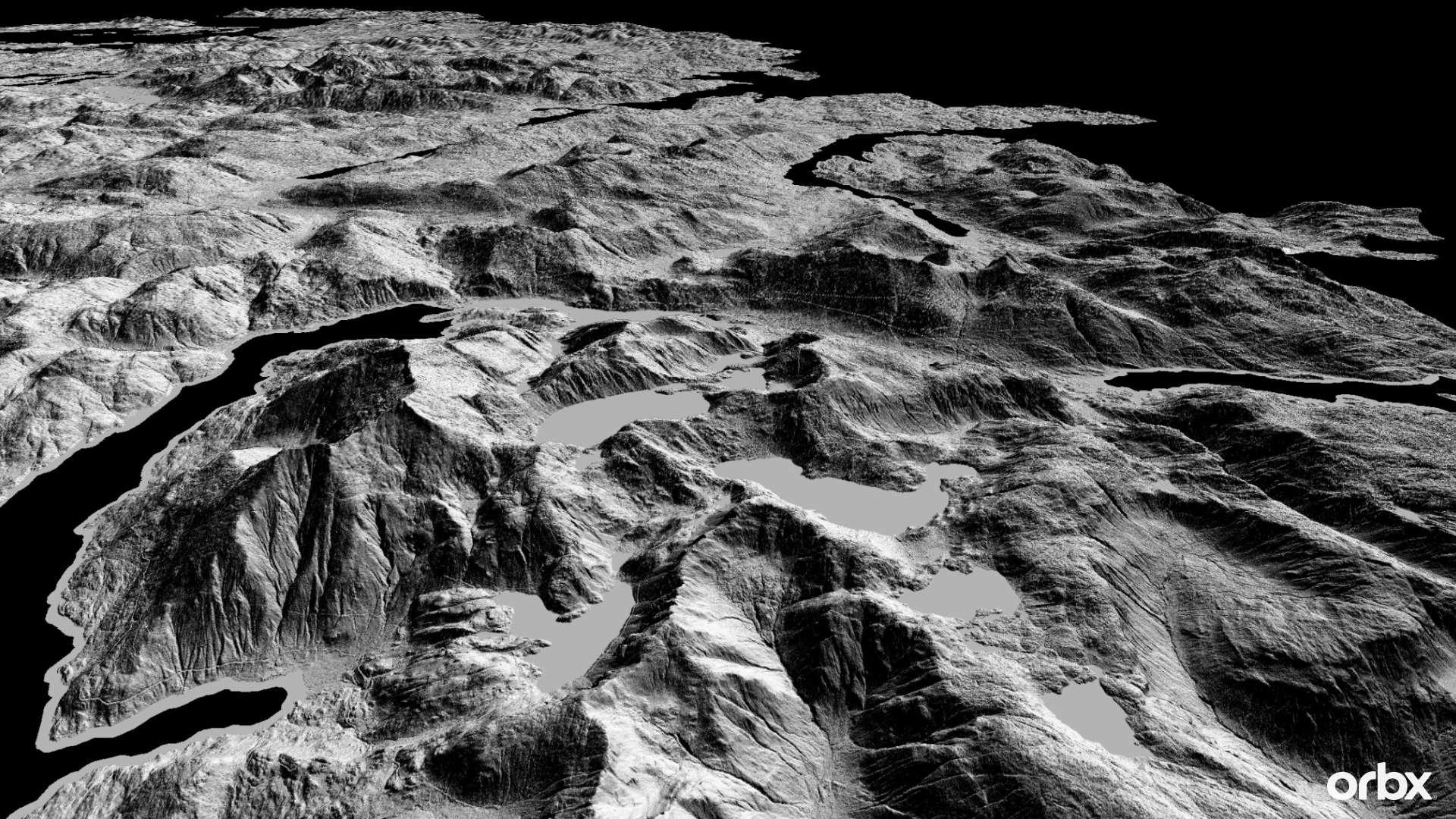

Holger: In some cases, the data is used directly (perhaps with minor editing), for example, elevation data is used to compile terrain heightfield files for MSFS, or aerial imagery is used to compile orthoimagery files for TrueEarth regions for X-Plane.

In other cases, a lot of filtering or editing is required when the source data is either too detailed for direct use or has obvious errors or missing entries. In those cases, we typically look for similar datasets that can help with fixing the issues or we’re manually doing additional prep work.

A third approach is to not use the source data directly but rather generate our own data layers, using a combination of existing data and environmental modeling/scripting.

Giuseppe: How do you source the geospatial data you work with? Do you rely on external providers?

Holger: Yes, in most cases we utilize external providers like government and private entities. Fortunately, an increasing number of high-quality global and regional data sets are available free of charge.

Many countries and states now maintain “Open Data” websites that allow anyone to access and use their data sets, including for commercial use. It’s primarily about being aware of where to look or whom to contact.

In addition, we have long-standing relationships with commercial data resellers whom we engage if we need to pay for licensing specific types of data.

Giuseppe: Do you ever generate your own geospatial data?

Holger: As a matter of fact, we do. In some cases no suitable data sources exist and we use other types of data, along with some clever scripts and tools of our own, to generate what we need.

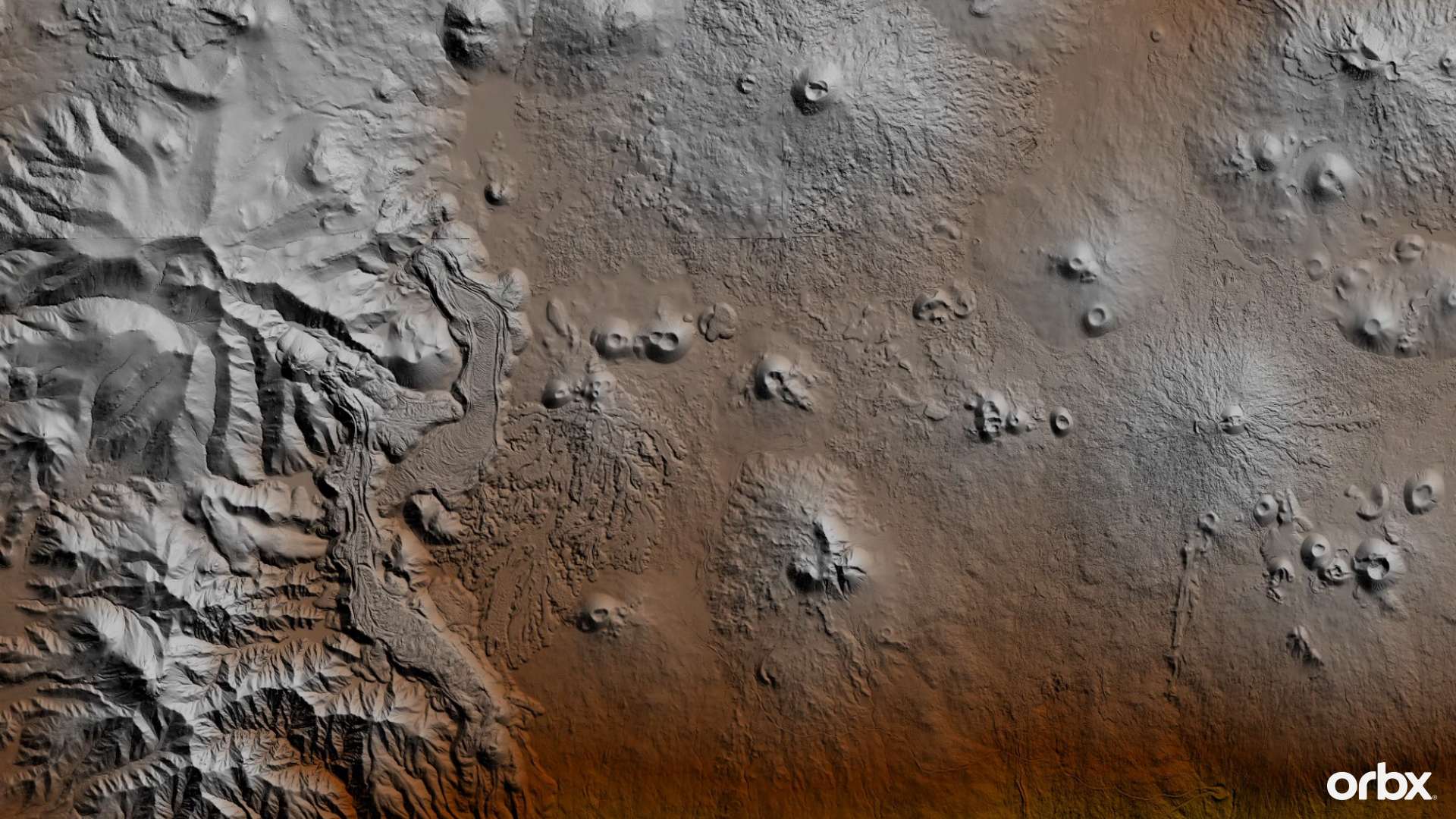

For example, for the Kola map that we released for DCS World we didn’t have high-resolution orthoimagery available (it was either too expensive or not usable). Instead, we used synthetic satellite imagery, height data, slope gradients, climate data, etc., in conjunction with environmental modeling, to generate a high-quality set of ground textures that place the landscape elements in the right places and look like orthoimagery but don’t suffer their common issues of baked-in shadows, cloud imprints, or inconsistent coloring due to different capture dates.

Giuseppe: How is the data processed to be used in flight simulation add-ons?

Holger: Typically, there are three stages:

First of all, the raw source data has to be prepared: clipped to the area of interest, checked for errors, and its spatial projection changed to match the respective simulator’s projection. This usually happens in standard GIS (Geographic Information Software) applications.

Then we use our own or third-party tools and scripts to transfer the data into the SDK (Software Development Kit) apps, which then we use to compile the source into the specific file formats and folder structure of the simulator.

Finally, extensive checking and manual editing take place to make sure that the new additions to the base terrain match the expectations of the developers and users.

Giuseppe: Microsoft Flight Simulator has brought a lot of innovation in the way the world is displayed. How did it change the way you work with geospatial data, if any?

Holger: It has shifted quite a bit. For example, orthoimagery is now a global feature of the base sim and it is no longer required other than perhaps in local areas for which custom high-resolution ground textures are needed.

On the other hand, local terraforming is now possible at higher precision, which allows for more detailed shaping of the local terrain.

Last but not least, Orbx has become a first-party provider for the base Mirosoft Flight Simulator itself, delivering several World Updates as well as global elevation data and vertical obstructions.

Giuseppe: I imagine you’re likely not at liberty to say much about the work Orbx is doing on Microsoft Flight Simulator 2024, but could you give us an overview, as far as you’re allowed to share?

Holger: As Jorg and I presented at FSExpo in Las Vegas in June 2024, Orbx is responsible for discovering and processing the best available global elevation data (DEM), as well as creating a global database of vertical obstructions, including antennas, chimneys, wind turbines, and powerline towers.

The DEM collection effort has been an active project for several years now and that data is also used in the shaded terrain display in Bing Maps and other MS applications.

The vertical obstructions project is a more recent collaboration with a Polish team that is well regarded for its “We Love VFR” series of freeware add-ons, called Puffin Flight. Both projects are or will be integrated into MSFS2020 and MSFS2024.

Giuseppe: That must require a mind-boggling quantity of data. Could you elaborate on the challenges of finding it for the whole world?

Holger: Indeed, for the elevation data project we’ve processed several hundred terabytes of source data to date, and the vertical obstructions project involves millions of individual structures.

Finding data sources that aren’t publicly listed requires quite a bit of detective work, primarily by contacting agencies and individuals of the respective territories. Many gaps still exist (especially for Africa and parts of Asia and South America).

The more challenging aspects are data storage and processing, and determining the correct approach to “distilling” and refining the source data into usable files. Moreover, many sources are either non-public or too expensive for these projects and thus we have to come up with clever ways to find or generate stand-in data of similar quality.

Last but not least, all data sources need to be verified by Microsoft Legal for licensing conditions and attributions, which requires careful documentation of all sources by our teams.

Giuseppe: Both Microsoft Flight Simulator and Microsoft Flight Simulator 2024 are basically digital twins of Earth. Do you think this kind of application of geospatial data is going to become more widespread in entertainment and business?

Holger: Absolutely. Again, the challenge will be in finding meaningful applications of the vast quantities of data. It’s not too difficult to create a (static) Digital Twin of anything these days.

The question is what to do with it beyond looking at something in three dimensions. Static models of natural or manmade things are not really digital twins, in my opinion.

Giuseppe: Has there ever been a particular location or set of data that you found particularly challenging to find or to work with?

Holger: Generally, challenging means more interesting, as it forces us to think creatively about filling gaps, fixing issues, or generating data from limited sources. On the other hand, limitations of a simulator’s “terrain engine” can also be a source of intense frustration and moments of despair.

The most recent example for us is the development of the vast northern European Kola Map add-on for the Digital Combat Simulator – from scratch – which took a lot of trial and error, sweat and tears, and dogged determination, over the course of two years!

In particular, the basic terrain mesh and lakes, rivers, and shorelines, which in X-Plane or Prepar3D take a week or two to integrate, took months and months of experimentation and compromises.

Giuseppe: Does Orbx use geospatial data in other areas besides creating add-ons for flight simulators?

Holger: Yes, we have employed geospatial data in several projects for private companies, and others are ongoing.

Giuseppe: How do you expect the technology used to gather geospatial data and the data itself to evolve in the semi-near future? Is there any exciting innovation on the horizon?

Holger: One example is the increasing availability of high-precision LiDAR data. The original point clouds of the laser scans get processed into layers with surface features (buildings, vegetation, etc.), and bare earth.

This means that the height differences between the two can be used to derive the heights of individual trees, buildings, and other structures, which in turn means one can accurately scale large numbers of objects for placement.

Giuseppe: Thank you for your time Holger. I’m sure our readers will love the insight.

If you want to know more, head to https://orbx.co/ or write to [email protected].